Jan 21st was a hot, hot day. Probably not the best sort of day to go on a 5km walk through the concrete byways of the city,. But walk we did and all 12 of us had a great time. In fact I think if you can do this kind of walk, with a camera and still come back with a couple of good, strong images, you can do it anywhere.

Jan 21st was a hot, hot day. Probably not the best sort of day to go on a 5km walk through the concrete byways of the city,. But walk we did and all 12 of us had a great time. In fact I think if you can do this kind of walk, with a camera and still come back with a couple of good, strong images, you can do it anywhere. That's a bit of an assault course mentality but I think doing this can stand you in good stead, providing you don't get too much sun. I suggested we shoot bracketed exposures as much as possible. Firstly, to help combat the extreme contrast experienced on a day that's 30 degrees in the shade.

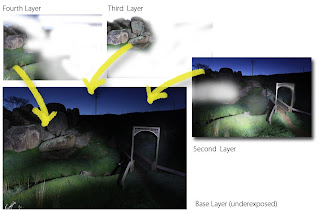

That's a bit of an assault course mentality but I think doing this can stand you in good stead, providing you don't get too much sun. I suggested we shoot bracketed exposures as much as possible. Firstly, to help combat the extreme contrast experienced on a day that's 30 degrees in the shade.And secondly with a mind to use all three/four/five/seven bracketed shots in an HDR image at some later date.

HDR? High Dynamic Range image.

HDR? High Dynamic Range image.This is really a 'super tone' image in that, using specific software, allows you to take all the 'good' bits from the three bracketed shots and assemble them into one super tone image that has a much wider range of tones in it that you could possibly capture with the one shot.

The reason this is necessary is that our cameras cannot capture a wider dynamic range than about 5-7 f-stops (depending on who you talk to).

(Here's MB with a new camera-steadying technique)

A general scene shot on an extremely bright, sunny day is likely to have a dynamic range of 10-12 steps (that's ranging from extreme white highlights to

dark shade). This nicely explains why some of your landscapes have great skies but lousy dark landmasses in them. Why interior shots often have white, blown-out detail in windows and why family groups always look so bad if the people are standing in dappled light.

dark shade). This nicely explains why some of your landscapes have great skies but lousy dark landmasses in them. Why interior shots often have white, blown-out detail in windows and why family groups always look so bad if the people are standing in dappled light.The best software for assembling and manipulating HDR images is called Photomatix Pro and is available as a free demo from www.hdrsoft.com - it only costs US$99 so, if you like what you see, I think it's well worth buying - if you don't the trial version puts a PHOTOMATIX watermark through each picture! Photoshop CS2/3/4 also does the HDR merging but, in my opinion, the results area not quite as spectacular.

You can also use Elements (any version) you can also assemble a credible HDR effect - although as you'll see from the PDF I'll send to all that took part in the walk, it's not that easy to do. It's a complex and involved 'workaround'. Good news is that in version 8.0 you'll find a NEW feature called Photomerge Exposure (under the File>New>Photomerge menu) which does an OK job of either automatically or manually making the effect. Again, I don't think it is a patch on Photomatix Pro but, if you have Elements 8.0, give it a go. See my pathetically small video on this page for some assistance...

We also had some fun shooting the evening light as it faded opposite the city at the end of the walk - some using Polarising filters of ND filters to deliberately slow the shutter speed to excessively long times so as to create a smoother and more glass-like appearence to the slightly choppy harbour waters.